Unlearning

I consider myself an educated person. I’ve always valued learning. It was instilled in me from a young age by my parents and by my surroundings. My Dad used to say that education is the silver bullet to, well, everything.

He believed unequivocally that if you are educated, you will get ahead. That’s why he encouraged me to excel academically. I remember the first day of school, either first or second grade, and he asked me to spell the word best. I was so nervous for school to start, I couldn’t remember. I was flummoxed by the word. I stuttered and stammered and eventually, he told me - B.E.S.T. It became a bit between him and me. Whenever I was feeling stressed about school (or pretty much anything else), he would ask, Alyson, how do you spell best? And, either smiling or grumbling, I would answer - B.E.S.T!

I have mixed feelings about that memory. On the one hand, I love that it brought him joy over the years. I love that he saw me as full of potential, as a person who could do anything and be anything. On the other, that’s probably the memory I can point back to as being the place I learned that I would always need to do well academically to please him. That his love and joy, whether true or not, was tied up in my education and being smart - being the B.E.S.T.

So, it’s no wonder to me that I’ve always tried to be really smart, to never make mistakes. That I aimed for perfect grades in high school (and got pretty close). I eased up on myself a bit in college, knowing a G.P.A. wasn’t everything anymore, but I still worked really hard academically. I did the B.E.S.T. that I could and took that with me into the ‘real world.’

My B.E.S.T. has always been good - more than good. I’m an overachiever. I want people to appreciate me and think of me as being smart and talented. I go above and beyond every chance I get, and then say it’s no big deal, when, in fact, I’m left depleted at best and burned out at worst.

Why do I do this to myself?

Because that’s what I’ve learned to do in a capitalistic, patriarchal, and white-supremacist society.

All three of these systems come into play when I write about burnout and toxic productivity, and even care as I did two weeks ago. These systems are the reason why unpaid labor is not valued, why women bear the load of caregiving, and why people of color are oppressed more than anyone else. These systems are why, when a Black 16-year-old boy going to pick up his siblings goes to the wrong house, he can be shot in the head by an 84-year-old white man who will then claim self-defense.

Our systems are designed to support only certain kinds of people, which means a whole lot of us are forced to try to keep up any way that we can or are left out, dealing with the structural oppression of those systems. Even the people who benefit most from these systems are trapped by these systems.

I’m not an expert in any of this. There are entire graduate degrees devoted to understanding these systems. And I’m probably not going to be going back to school any time soon.

But I am unlearning a lot of what I’ve been taught over my lifetime. I’m imagining a new way of engaging in the world and with each other. A way that doesn’t center on any one race or gender or salary.

My journey of unlearning started six years. I could start that journey of unlearning because of my privilege, and it’s something I will always acknowledge. You might want to unlearn these things too, but you might not have the same privileges that I do. What follows is a story of my personal journey that (hopefully) gives you permission and encouragement to start your journey, wherever that may be.

Even if, for now, you’re only starting with curiosity about why someone like me believes this. That’s enough.

Because you can only start from where you are.

When the 2016 election results came in, I started asking questions. How did that election result happen? How did our country elect someone like him? Is this real?

It didn’t make sense to me at the time. It makes more sense to me now. I’ve read a lot to help me answer those questions, which led me down a path of understanding more about how the systems are designed and who they benefit.

It’s not pretty. It’s not easy. There is nothing simple about how we got here and why it matters. Why it impacts each and everyone one of us.

My journey to learn why the 2016 election unfolded the way it did started in the only place that made sense to me — with history.

My first teachers on this journey were Nancy MacLean and Carol Anderson. MacLean’s book, Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America, is foundational for my understanding of the roots of the far-right movement in the United States that started decades ago. It’s where I found answers to some of my questions about the 2016 election and all that followed.

I found more answers in Anderson’s White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. There are so many things in this book that I never knew, but there is one that has stuck with me more than any other.

Both of these books discuss Brown v. Board of Education as being a pivotal event in our racial and political history as a country. We all learned about this 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision that desegregated public schools. It was a victory for civil rights, wasn’t it?

“At that moment, it appeared that citizenship — true citizenship — might finally be at hand for African Americans.” (See note 1)

Sure, there was some resistance and yes, violence, to its implementation. The murder of Emmett Till, the “angry mob of housewives surrounding traumatized Elizabeth Eckford on the first day of school at Central High in Little Rock” (see note 2) and who of us hasn’t seen the painting by Normal Rockwell of Ruby Bridges being escorted by U.S. Marshalls? But, the schools were integrated and Brown is the law of the land, and that’s that. Or so I thought until I read these two books.

While MacLean discusses at length the political strategy spurred by the Brown decision, Anderson puts the impact of the backlash concretely. White Southerns in positions of power — from school board members to governors — shut down public schools.

My Mom was six years old, going into first grade when Brown was handed down. She is white, lived outside of the South, and attended public schools without issue or disruption. That’s her privilege. But the kids the same age as my Mom, who didn’t have the same color skin and who didn’t live where she did — some of them didn’t get a public school education at all.

For example:

“Between donations totaling more than $300,000, state funding of $176 per year per student, and taxpayer-subsidized busing to private academies, Little Rock had the means for most white children to remain in school while the state simultaneously defied the Supreme Court by keeping blacks locked out.” (see note 3)

Prince Edward County in Virginia went further for longer — their public schools were shut down for five years. “While white children were educated, 2,700 black children were locked out.” (see note 4) And while some Black families were able to send their children to other places, only 35 of them “were able to attend those out-of-state schools on a full-time basis.” (see note 5)

[This strategy, by the way, of threatening to or shutting down something rather than complying with court decisions, is still being used today.]

Of course, Black people in Prince Edward County did not sit on their hands and let this happen. They took action. They put together activity and education centers, creating what they could for their children’s futures.

It wasn’t until 1964, ten years after Brown, that Prince Edward County public schools were forced to comply with Supreme Court decisions and reopen to all students. (see note 6)

I didn’t know any of this had happened. And I studied history in college. How did I not know this until I read White Rage?!?!

While I’m grateful for the education I’ve received because it helped me think critically, I’m often angry about that education as well. How did I not know this about the aftermath of Brown v. Board of Education? What else don’t I know? What else about the lived experience of my fellow Americans (and humans) don’t I know or understand?

And what can I do to change it?

This is where my journey of learning shifted into a journey of unlearning. One that I realize is complicated and messy and full of uncertainty and mistakes and, above all, ongoing.

I will never unlearn it all. I will never not make mistakes when it comes to being anti-racist or a good ally. I was born into a lower-middle-class, white, heteronormative family in a capitalistic, patriarchal, white supremacist society. There is A LOT to unlearn with that history.

There is a lot to admit with that history too. Including acknowledging that I perpetuate these oppressive systems.

I don’t want to admit complacency in this any more than you probably do. None of us want to admit we are flawed. That we have racist thoughts or have done racist things, whether intentionally or not. That we don’t always support others getting ahead or doing better than us. It takes deep, personal work to face these things, to understand where they come from and why. It’s a personal journey that you have to want to take.

And I hope you want to take that journey because we’re never going to get anywhere without you. We’re never going to imagine and create a new world separately from one another.

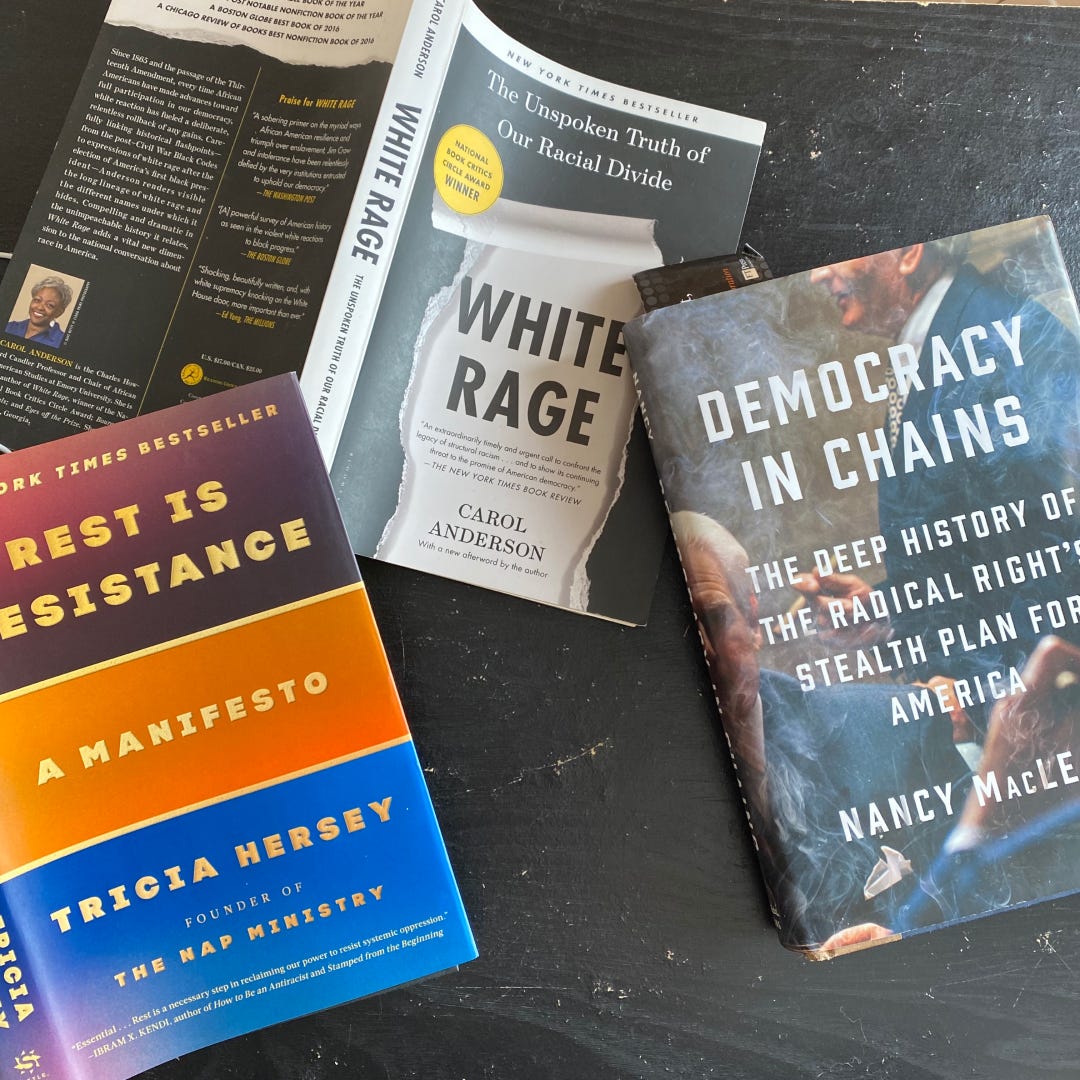

A few weeks ago, on the first real sunny, warm-ish (it was 32 degrees) day this year, I sat on my back deck and read Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto by Tricia Hersey. It’s been a very long time since I finished a book in one seating. There is a rhythm to her book that is mesmerizing. She calls it a manifesto for a reason. Much of what she writes is intentionally repetitive.

My husband was the one who actually told me about Hersey’s book. He heard an interview on NPR with Hersey and felt like everything she said was right up my alley. He was absolutely correct. I’m deeply grateful that the universe conspired to bring me to her book and her wisdom.

Hersey is a performance artist, writer, theater maker, activist, theologian, and daydreamer. She is the founder of The Nap Ministry, which she started developing during graduate school. Facing exhaustion and uncertainty about her next steps after grad school, she started talking about “creating an art piece on rest.” That idea turned into the first Collective Napping Experience, which are “in-person and virtual spaces for us to rest together, to hold space for each other and to enter the portal of rest as a sacred act.” (see note 7) Hersey identifies herself as the Nap Bishop.

The Nap Ministry, her manifesto, and everything Hersey speaks to are about so much more than napping. It is a protest.

“This protest against grind culture is for you to create in your own body. Your body is yours. It’s uniqueness and stories it has to tell are yours. A community call toward rest as a form of activism is a call to slow down and listen and care. It is an empowered place fueled by the shared goal of becoming more human. We are not machines. We are not on Earth to fulfill the desires of an abusive system via our exhaustion.” (see note 8)

Hersey makes it very clear where her foundation for this protest comes from, and what grounds her work. Some of the concepts were new to me, like womanism. Another is Black liberation.

As a white woman, I can honestly say that it took years of unlearning to be able to read Hersey’s book with openness and acceptance. If I had only recently started this journey of unlearning and understanding, her manifesto would have been jarring and unsettling and I would have received it from a place of defensiveness. Even now, some of her wisdom makes me uncomfortable, but I have reached a place where I can be comfortable in that discomfort. If I’m experiencing that, I know I’m still unlearning — still growing. Which is the whole point of all of this for me.

And it’s why I can understand why Hersey writes:

“I have spent the entirety of my life as the Nap Bishop answering this question: “Is the Nap Ministry just for Black people?” The question itself stems from a white supremacist mindset that refuses to accept this truth: Black liberation is a balm for all humanity and this message is for all those suffering from the ways of white supremacy and capitalism. Everyone on the planet, including the planet itself, is indeed suffering from these two systems.” (see note 9)

If I ever feel like I’m responding from a place of defensiveness now, I try to pause and ask myself why. Why do I feel defensive when a Black person calls out white people or white supremacy? Why do I feel uncomfortable when someone starts off a message with Dear Black people, Dear Queer people or Dear anyone-but-my-own-identifiers people?

It’s because those all decenter me, a place I’m not used to as a white, cisgender woman. It’s because I am no longer the B.E.S.T.

This is a delicate point I’m trying to make and one that you may not agree with. That’s okay. I may be screwing all of this up and that’s okay too — it’s part of my journey.

I understand this framing now, about who is centered and who isn’t, because I read a lot and listen more. And I read and listen to mostly Black women and women of color. I don’t say this to be performative, but to acknowledge their wisdom and insight into the societal systems that we all contend with. Most of what I’ve learned in my unlearning journey comes from these authors, writers, poets, thought leaders, and everyday humans who experience the world differently than I do. Who the world treats differently.

It’s why I now understand, without defensiveness, that yes, Black liberation is liberation for all, as Tricia Hersey so beautifully describes:

“Community care and a full communal unraveling is the ultimate goal for any justice work, because without this we will be left vulnerable to the lie of toxic individualism. Our justice leaders have been screaming this from the rooftops for centuries and yet our toxic individualisms, residing in an exhausted, brainwashed mind, continues to ignore this life-giving wisdom…When we function thinking only of ourselves and believing we can do it alone, we create harm and create a container for more exhaustion.” (see note 10)

I know this intimately. Trying to do it all, amid systems and structures designed to keep you from keeping up, is what led me to burn out so significantly two years ago.

Learning the history that I never knew drove me to invest even more of myself in my political work that started after the 2016 election, even if the systems chewed me up and spit me out.

Because that’s the other point of this journey of unlearning — you can’t dismantle the systems by doing what the systems are designed for. You have to be imaginative. (see note 11) You have to try new things. And if you’re trying to do it alone, it’s never going to work.

That’s what I learned from my burnout. My political work mattered deeply to me, to the point that I was putting it before anything else, including my health and my relationships. Had I read Rest is Resistance in 2021, I would have scoffed at it. I can’t take a nap every day, are you kidding me? I have waaaay too much to do. I have to work to change the system!

Which is how the system keeps you in the system.

The books I read, the writers I follow, and the people I look to (whether they know it or not) all help me understand how the world is right now and give me ideas of how you and I can change it, if we so choose. They are my teachers, and like any good student, it is up to me to put into action what I’ve unlearned.

It is up to me to create something from that unlearning.

It’s why I’m here today, writing this meandering essay. Join me on this journey. Start somewhere. Start with Democracy in Chains or White Rage or Caste or Mothers of Massive Resistance. Or maybe there is another place besides history that you want to start. Maybe it’s adrienne maree brown and their work on emergent strategy or reading novels that center non-white people in the story. Maybe it’s just being curious enough to keep reading this newsletter to see what other radical things I’m going to write and where I go with this. Maybe it’s simply finding and following other people who write about this from their perspective.

Wherever you start, the point is to start.

And if you do start, remember: your B.E.S.T. doesn’t mean you are the best or will be the best because of this unlearning journey. You’re going to fuck up. You’re going to get defensive. You will be uncomfortable. It’s going to be hard and frustrating and some people will look at you funny when you get to the point where you rage against capitalism and the patriarchy and white supremacy. Some people will think you’re too ‘woke’ for you’re own good.

But what you’re really doing is changing the world, one funny look and difficult conversation at a time.

And what it means is that your B.E.S.T. is enough. That you are enough.

Notes

Note 1: Anderson, Carol. White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide. New York, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. p 75.

Note 2: Anderson, p. 75

Note 3: Anderson, p. 82.

Note 4: Anderson, p. 84.

Note 5: Anderson, p. 84.

Note 6: But not without ensuring that Prince Edward County public schools were 98 percent and lacking resources. See Anderson, p. 85.

Note 7: Hersey, Tricia. Rest is Resistance: A Manifesto. New York, Little Brown Spark, 2022. p. 65.

Note 8: Hersey, p. 67.

Note 9: Hersey, p. 75.

Note 10: Hersey, p. 76-77

Note 11: This is the whole point of Hersey’s manifesto — we have to use our imagination to see a new world is possible, and we have to be rested in order to use our imagination.